China’s population drops for the first time since 1960s famine

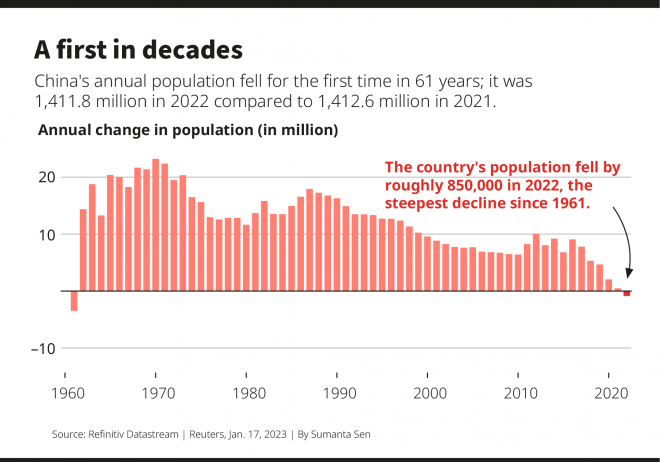

China’s population has decreased for the first time in over 60 years, signaling the start of long-term decline that will bring demographic challenges for the world’s second-largest economy as well as the world.

Last year, 9.56 million babies were born in China, while 10.41 billion people died, a yearly decrease of 850,000 to 1,411,750,000 people, according to data published by China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

It was the first decline since 1961, the final year of the famine brought on by failing economic policies during Mao Zedong’s “Great Leap Forward,” the campaign to transform China from a mostly agrarian society into an industrial that ended in disaster.

India may now be the most populous country on Earth, Reuters reported, with an estimated population of 1.42 billion, though pandemic-related delays in that country’s census have yet to confirm the actual total.

The long-term outlook for China, according to U.N. experts, is that the population will continue to decrease by about 109 million people to 1.3 billion by 2050.

The turning point puts China in a similar situation as regional neighbor Japan, whose population has been shrinking, and South Korea, where birth rates are declining after rapid economic growth, leaving fewer young people in the workforce to support a swelling number of retirees. That has put a larger tax burden on workers and could lead to economic stagnation.

Already, China’s economy is slowing. From a peak of 14.2% growth in 2007, its 2022 figure was a mere 3%, less than half the growth rate of 2021 and the lowest in almost 40 years.

![]()

Policy and pessimism

The demographic shift reflects both the results of China’s one-child policy and a pessimism about the future, experts said.

An unintended consequence of the one-child policy, which lasted from 1980 to 2015, combined with a cultural preference for boys, has led to a major gender imbalance, resulting in fewer possible families being formed, especially in rural areas.

This policy “broke the normal ecological balance of China’s population,” said Chen Guangcheng, a civil rights activist.

But there is also an economic and psychological element contributing to this trend. Combined with skyrocketing housing and education prices that come with robust economic growth, many young Chinese today simply do not envision children in their future.

“A decline in the willingness to have children reflects the hardships of Chinese people’s daily lives,” Wu Qiang, a Beijing-based scholar who focuses on population, told RFA’s Mandarin Service. “This is a reflection of their pessimism about the future.”

And the recent surge in COVID-19-related deaths has driven home China’s demographic dynamics.

“Almost every family is mourning the loss of loved ones,” Wu said. ”To most citizens it’s not just a statistical figure; it’s a deep, painful cut."

As fewer Chinese enter the workforce and more age out, the result will be that economic growth will be dependent on productivity increases, Zhiwei Zhang, chief economist at Pinpoint Asset Management, told Reuters.

China, whose rapid growth as the world’s factory floor led it to surpass Japan as the world’s second-largest economy in 2010, is bound to see its economic growth decline, said Yi Fuxian, a scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“I predict that by 2030 to 2035, China"s economic growth rate will be lower than that of the United States,” he said.

![]()

How to stimulate population growth?

Since the end of the one-child policy, China, like South Korea and Japan, has enacted policies meant to encourage young people to have children, including housing and tax incentives and longer parental leave, but these have not proved effective.

Yi said that China’s attempts to stimulate birth rates will be even less successful than they have in Japan, because China’s government has fewer resources.

“I predict that if the Chinese government does not carry out earth-shaking reforms, in the next few decades or even hundreds of years, China’s population will continue to shrink,” said Yi.

Chen Guangcheng believes that the party may indeed enact extreme policies to increase the population.

“The problem now is that the declining population will expand rapidly in the future. Therefore, if it were not for the Chinese Communist Party’s intervention and violent destruction, today’s [population problems] would not be possible,” Chen said.

“[These] various methods that can be imagined or unexpected, changing [the Party’s] violent family planning into violent forced birth policy. It is very possible,” Chen said.

The population decline may have started earlier than 2022, and Chinese authorities are only now acknowledging it, Gao Yang, an independent journalist who reports on population and family planning policies, told RFA.

Gao suspects the authenticity of Chinese government population statistics, especially with a rapid increase in deaths during the coronavirus pandemic.

“I personally think population decline began several years ago and gradually developed to its current very serious extent before finally having to be admitted,” said Gao.

“A sharp population decline is not nine years down the road, as some experts predicted, but will in fact begin this year,” he said. “2023 could mark the start of serious, long-term population decline."

Translated by Chase Bodiford, Jerry Zhao, Tian Li, and Laura Huang. Written in English by Eugene Whong. Edited by Malcolm Foster.

[圖擷取自網路,如有疑問請私訊]

Last year, 9.56 million babies were born in China, while 10.41 billion people died, a yearly decrease of 850,000 to 1,411,750,000 people, according to data published by China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

It was the first decline since 1961, the final year of the famine brought on by failing economic policies during Mao Zedong’s “Great Leap Forward,” the campaign to transform China from a mostly agrarian society into an industrial that ended in disaster.

India may now be the most populous country on Earth, Reuters reported, with an estimated population of 1.42 billion, though pandemic-related delays in that country’s census have yet to confirm the actual total.

The long-term outlook for China, according to U.N. experts, is that the population will continue to decrease by about 109 million people to 1.3 billion by 2050.

The turning point puts China in a similar situation as regional neighbor Japan, whose population has been shrinking, and South Korea, where birth rates are declining after rapid economic growth, leaving fewer young people in the workforce to support a swelling number of retirees. That has put a larger tax burden on workers and could lead to economic stagnation.

Already, China’s economy is slowing. From a peak of 14.2% growth in 2007, its 2022 figure was a mere 3%, less than half the growth rate of 2021 and the lowest in almost 40 years.

Policy and pessimism

The demographic shift reflects both the results of China’s one-child policy and a pessimism about the future, experts said.

An unintended consequence of the one-child policy, which lasted from 1980 to 2015, combined with a cultural preference for boys, has led to a major gender imbalance, resulting in fewer possible families being formed, especially in rural areas.

This policy “broke the normal ecological balance of China’s population,” said Chen Guangcheng, a civil rights activist.

But there is also an economic and psychological element contributing to this trend. Combined with skyrocketing housing and education prices that come with robust economic growth, many young Chinese today simply do not envision children in their future.

“A decline in the willingness to have children reflects the hardships of Chinese people’s daily lives,” Wu Qiang, a Beijing-based scholar who focuses on population, told RFA’s Mandarin Service. “This is a reflection of their pessimism about the future.”

And the recent surge in COVID-19-related deaths has driven home China’s demographic dynamics.

“Almost every family is mourning the loss of loved ones,” Wu said. ”To most citizens it’s not just a statistical figure; it’s a deep, painful cut."

As fewer Chinese enter the workforce and more age out, the result will be that economic growth will be dependent on productivity increases, Zhiwei Zhang, chief economist at Pinpoint Asset Management, told Reuters.

China, whose rapid growth as the world’s factory floor led it to surpass Japan as the world’s second-largest economy in 2010, is bound to see its economic growth decline, said Yi Fuxian, a scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“I predict that by 2030 to 2035, China"s economic growth rate will be lower than that of the United States,” he said.

How to stimulate population growth?

Since the end of the one-child policy, China, like South Korea and Japan, has enacted policies meant to encourage young people to have children, including housing and tax incentives and longer parental leave, but these have not proved effective.

Yi said that China’s attempts to stimulate birth rates will be even less successful than they have in Japan, because China’s government has fewer resources.

“I predict that if the Chinese government does not carry out earth-shaking reforms, in the next few decades or even hundreds of years, China’s population will continue to shrink,” said Yi.

Chen Guangcheng believes that the party may indeed enact extreme policies to increase the population.

“The problem now is that the declining population will expand rapidly in the future. Therefore, if it were not for the Chinese Communist Party’s intervention and violent destruction, today’s [population problems] would not be possible,” Chen said.

“[These] various methods that can be imagined or unexpected, changing [the Party’s] violent family planning into violent forced birth policy. It is very possible,” Chen said.

The population decline may have started earlier than 2022, and Chinese authorities are only now acknowledging it, Gao Yang, an independent journalist who reports on population and family planning policies, told RFA.

Gao suspects the authenticity of Chinese government population statistics, especially with a rapid increase in deaths during the coronavirus pandemic.

“I personally think population decline began several years ago and gradually developed to its current very serious extent before finally having to be admitted,” said Gao.

“A sharp population decline is not nine years down the road, as some experts predicted, but will in fact begin this year,” he said. “2023 could mark the start of serious, long-term population decline."

Translated by Chase Bodiford, Jerry Zhao, Tian Li, and Laura Huang. Written in English by Eugene Whong. Edited by Malcolm Foster.

[圖擷取自網路,如有疑問請私訊]

|

本篇 |

不想錯過? 請追蹤FB專頁! |

| 喜歡這篇嗎?快分享吧! |

相關文章

AsianNewsCast