INTERVIEW: ‘Behind the shadows, they can do very brutal things’

Toru Kubota, a Japanese documentary filmmaker, was arrested by Myanmar military authorities on July 30 for filming a small anti-junta protest in Yangon. They accused the 26-year-old of violating Myanmar’s immigration laws and encouraging dissent against the army junta which has ruled the country since seizing power in a February 2021 coup. In all, Kubota was sentenced to 10 years in jail and was placed in Insein Prison on the outskirts of Yangon.

On Nov. 17, authorities released Kubota along with more than 6,000 others, including citizens detained for protesting the military takeover, during a broad prisoner amnesty. Kubota spoke with reporter Soe San Aung of Radio Free Asia’s Burmese service about his experiences. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

By Soe San Aung

RFA: Why were you in Myanmar?

Kubota: It’s not like I jumped into the country for the first time this time. I had been in the country more than 10 times before, but it was before the coup. I worked on several projects in Myanmar, including the Rohingya issue, so I really wanted to do something since the coup. And there were some friends who remained in the country doing amazing work; for example, helping other people by serving food to street people. This is the reason why I am making a film about my friend who is doing humanitarian work.

RFA: How has Myanmar changed for you since the coup?

Kubota: Once I started filming, it became obvious people were suppressed very silently. For example, I saw an old lady on the street clinging to my friends and weeping, telling them that she had been beaten by the police and that the police had taken her money. She was making her living by begging, and the police took what little money she had. The lady was weeping and telling this story, but at the same time she was really cautious about someone overhearing her telling the story. This is the situation in the country.

RFA: When the military junta detained you for six days, how did authorities treat you? Did they torture you?

Kubota: No, they didn’t torture me. I was also in custody after I was arrested and after the investigation, and it was kind of funny. They let me stay overnight in the chief officers room with air conditioning for the first night. The second night, they investigated me, but they didn’t punch, beat or physically harm me, But after they found my film, which was about the Rohingya, they felt very distressed. They looked at me in a really disgusted [manner] and stared at me as if to say, “I hate your film.” They told me I would be going to a place like hell. After that, I was taken to a detention cell, which was two meters by five meters and held more than 20 people. The smell was awful, and there was only one toilet. We didn’t have enough space for everyone to stretch our legs and arms, so we had to sleep with our bodies overlapping each other. I understood why they said that place is like hell. I stayed there a couple of days, and it was a really terrible place.

RFA: Why do you think the military regime is sensitive about your documentary about the Rohingya?

Kubota: It is like the Tatmadaw [Myanmar military] is protecting their own people, Buddhist people, from the Islamic forces invading their own territory. That was their strategy, and that was to secure their legitimacy. I think many people were fooled by that strategy as well and actually believed that the Rohingya Muslims were invading, and the military was protecting them. It worked very well for the Tatmadaw to stay in power, too. The police and the soldiers truly believe that we can use their enemies and that foreign journalists and filmmakers like me are by the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, by a huge mysterious fund.

RFA: What did the junta authorities ask you about your project?

Kubota: Where the money comes from. When I said that it was self-funded, they didn’t believe it. They repeatedly asked me [about it]. They pointed to the picture where I was at a film festival holding a very small glass trophy. [They asked] how much was that, or how much award money I got. I think they wanted to create a story that I was by some other foreign or Muslim forces or organizations. They also asked me about the contributors to the film, but they are not in the country anymore. I just told them the fact that they were not in Myanmar anymore. The other thing was just ordinary stuff like when did I make the [project]. They really wanted me to say that I was by some organization.

RFA: The junta’s spokesman said you were involved in the protest you filmed. Is that true?

Kubota: I did not participate in the protest. It is clear that I was filming from behind, [but] I did not have a direct connection to any of the protesters. So the fact is I was not involved in the protest, but after they arrested me, they told us to hold a [protest] banner. They told us to go in front of the police station and hold the banner that the protesters had been holding. They took a picture of us holding the banner, and they used it as evidence that I was one of the protesters. They even told me I wrote a banner statement, even though I don’t understand Burmese.

RFA: Tell us about your experience being detained in Yangon’s Insein Prison where you spent three months.

Kubota: What I went through as a foreigner was very mediocre compared to all the other Burmese people going through. I was myself in prison, just one person on my own in a two meter by four meter space. In my block there were 12 cells. In the daytime, I could spend time in the common space, the block area. I spent time studying Burmese. There was only one guy there who taught me Burmese, and I taught him Japanese. I was separated from all the political prisoners in Insein Prison, so I couldn’t get much information. But I saw prisoners secretly showing the three-fingered salute [of the popular protest movement against the junta] and saying “Fighting, fighting,” so I said, “Fighting.” Human interaction was going on in a very hidden way.

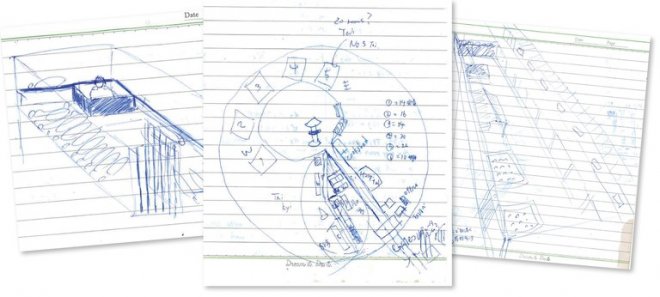

![]() Toru Kubota sketched the places where he was held in Myanmar. From left: A detention cell at a police station, Insein Prison and a block inside Insein Prison. Credit: Toru Kubota

Toru Kubota sketched the places where he was held in Myanmar. From left: A detention cell at a police station, Insein Prison and a block inside Insein Prison. Credit: Toru Kubota

RFA: Did you participate in any political prisoner protests during which the prison authorities suppressed inmates?

Kubota: I was on a hunger strike as well for the first six days while I was in detention because I needed to get in touch with the Japanese Embassy, but they didn’t let me do it. So, I told them that I would not eat until I could contact the embassy. But they didn’t beat me. They just gently tried to persuade me to eat, saying they were very worried about my health. I did not see the police or soldiers beating political prisoners.

RFA: You had been sentenced to 10 years in prison, but you were freed during the recent prisoner amnesty in November. Why do you think the junta released you?

Kubota: The first obvious reason is that the Japanese Embassy was pressuring them to release me. Another thing is that the junta used me and the other foreigners it released as propaganda tools to show international society that they became soft, and that the foreigner release is a ruse. Behind the shadows, they can do very brutal things. Our release can overshadow all the brutalities that are still ongoing. It is extremely shameful if I was used as a political tool to overshadow their brutality. Seven students from Dagon University were sentenced to death last week. They’re still killing their own people.

RFA: The Burmese people believe that the rest of the world remains silent about what is happening in Myanmar. As a foreigner, what do you think about what is going on?

Kubota: Burma has not attracted as much attention as Ukraine and other [countries] in the world. But what’s going on is the killings and massacre and genocide of the people. We shouldn’t be silent, saying this is an internal affair. These are crimes against humanity, so we should stand together. More specifically, we definitely should pressure the junta to stop killing people and release the prisoners. There are still more than 12,000 political prisoners detained, and I was one of them. We should continue paying attention to Burma.

RFA: There are some reports that the Japanese government has some business dealings with the junta, and activists are calling for it to cut funding to the junta. What should the Japanese government do?

Kubota: As many activists have pointed out, an organization called the Mekong Watch has also repeatedly pointed out the fact that Japan is being used by the junta. As Japanese citizens, we should be very responsible, and we need to speak out. At the same time we should accept as many refugees as possible from Burma. We haven’t even tried to accept any refugees. The number of refugees in Japan is very small, even though Japan is a country that signed the Refugee Convention.

RFA: Since the coup, the military has targeted not only anti-regime activists but also the media and journalists. Why do you think this is?

Kubota: They arrest and kill journalists in Burma because they want to cover up their ongoing brutality. They don’t want to let the world know about the massacre.

RFA: Will you ever go back to Myanmar?

Kubota: I really wish I could. I really want to support the people of Burma, but currently I cannot enter the country anymore. I might be able to go after the country becomes a place where I won’t be arrested, even though I was filming the protest. I really hope that the country will become a truly safe place for journalists so that we can do our jobs. But there are still many Burmese people working in the country, even though it’s extremely dangerous for them. I have enormous respect for each of them.

Written in English by Roseanne Gerin. Edited by Malcolm Foster.

[圖擷取自網路,如有疑問請私訊]

On Nov. 17, authorities released Kubota along with more than 6,000 others, including citizens detained for protesting the military takeover, during a broad prisoner amnesty. Kubota spoke with reporter Soe San Aung of Radio Free Asia’s Burmese service about his experiences. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

By Soe San Aung

RFA: Why were you in Myanmar?

Kubota: It’s not like I jumped into the country for the first time this time. I had been in the country more than 10 times before, but it was before the coup. I worked on several projects in Myanmar, including the Rohingya issue, so I really wanted to do something since the coup. And there were some friends who remained in the country doing amazing work; for example, helping other people by serving food to street people. This is the reason why I am making a film about my friend who is doing humanitarian work.

RFA: How has Myanmar changed for you since the coup?

Kubota: Once I started filming, it became obvious people were suppressed very silently. For example, I saw an old lady on the street clinging to my friends and weeping, telling them that she had been beaten by the police and that the police had taken her money. She was making her living by begging, and the police took what little money she had. The lady was weeping and telling this story, but at the same time she was really cautious about someone overhearing her telling the story. This is the situation in the country.

RFA: When the military junta detained you for six days, how did authorities treat you? Did they torture you?

Kubota: No, they didn’t torture me. I was also in custody after I was arrested and after the investigation, and it was kind of funny. They let me stay overnight in the chief officers room with air conditioning for the first night. The second night, they investigated me, but they didn’t punch, beat or physically harm me, But after they found my film, which was about the Rohingya, they felt very distressed. They looked at me in a really disgusted [manner] and stared at me as if to say, “I hate your film.” They told me I would be going to a place like hell. After that, I was taken to a detention cell, which was two meters by five meters and held more than 20 people. The smell was awful, and there was only one toilet. We didn’t have enough space for everyone to stretch our legs and arms, so we had to sleep with our bodies overlapping each other. I understood why they said that place is like hell. I stayed there a couple of days, and it was a really terrible place.

RFA: Why do you think the military regime is sensitive about your documentary about the Rohingya?

Kubota: It is like the Tatmadaw [Myanmar military] is protecting their own people, Buddhist people, from the Islamic forces invading their own territory. That was their strategy, and that was to secure their legitimacy. I think many people were fooled by that strategy as well and actually believed that the Rohingya Muslims were invading, and the military was protecting them. It worked very well for the Tatmadaw to stay in power, too. The police and the soldiers truly believe that we can use their enemies and that foreign journalists and filmmakers like me are by the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, by a huge mysterious fund.

RFA: What did the junta authorities ask you about your project?

Kubota: Where the money comes from. When I said that it was self-funded, they didn’t believe it. They repeatedly asked me [about it]. They pointed to the picture where I was at a film festival holding a very small glass trophy. [They asked] how much was that, or how much award money I got. I think they wanted to create a story that I was by some other foreign or Muslim forces or organizations. They also asked me about the contributors to the film, but they are not in the country anymore. I just told them the fact that they were not in Myanmar anymore. The other thing was just ordinary stuff like when did I make the [project]. They really wanted me to say that I was by some organization.

RFA: The junta’s spokesman said you were involved in the protest you filmed. Is that true?

Kubota: I did not participate in the protest. It is clear that I was filming from behind, [but] I did not have a direct connection to any of the protesters. So the fact is I was not involved in the protest, but after they arrested me, they told us to hold a [protest] banner. They told us to go in front of the police station and hold the banner that the protesters had been holding. They took a picture of us holding the banner, and they used it as evidence that I was one of the protesters. They even told me I wrote a banner statement, even though I don’t understand Burmese.

RFA: Tell us about your experience being detained in Yangon’s Insein Prison where you spent three months.

Kubota: What I went through as a foreigner was very mediocre compared to all the other Burmese people going through. I was myself in prison, just one person on my own in a two meter by four meter space. In my block there were 12 cells. In the daytime, I could spend time in the common space, the block area. I spent time studying Burmese. There was only one guy there who taught me Burmese, and I taught him Japanese. I was separated from all the political prisoners in Insein Prison, so I couldn’t get much information. But I saw prisoners secretly showing the three-fingered salute [of the popular protest movement against the junta] and saying “Fighting, fighting,” so I said, “Fighting.” Human interaction was going on in a very hidden way.

Toru Kubota sketched the places where he was held in Myanmar. From left: A detention cell at a police station, Insein Prison and a block inside Insein Prison. Credit: Toru Kubota

Toru Kubota sketched the places where he was held in Myanmar. From left: A detention cell at a police station, Insein Prison and a block inside Insein Prison. Credit: Toru KubotaRFA: Did you participate in any political prisoner protests during which the prison authorities suppressed inmates?

Kubota: I was on a hunger strike as well for the first six days while I was in detention because I needed to get in touch with the Japanese Embassy, but they didn’t let me do it. So, I told them that I would not eat until I could contact the embassy. But they didn’t beat me. They just gently tried to persuade me to eat, saying they were very worried about my health. I did not see the police or soldiers beating political prisoners.

RFA: You had been sentenced to 10 years in prison, but you were freed during the recent prisoner amnesty in November. Why do you think the junta released you?

Kubota: The first obvious reason is that the Japanese Embassy was pressuring them to release me. Another thing is that the junta used me and the other foreigners it released as propaganda tools to show international society that they became soft, and that the foreigner release is a ruse. Behind the shadows, they can do very brutal things. Our release can overshadow all the brutalities that are still ongoing. It is extremely shameful if I was used as a political tool to overshadow their brutality. Seven students from Dagon University were sentenced to death last week. They’re still killing their own people.

RFA: The Burmese people believe that the rest of the world remains silent about what is happening in Myanmar. As a foreigner, what do you think about what is going on?

Kubota: Burma has not attracted as much attention as Ukraine and other [countries] in the world. But what’s going on is the killings and massacre and genocide of the people. We shouldn’t be silent, saying this is an internal affair. These are crimes against humanity, so we should stand together. More specifically, we definitely should pressure the junta to stop killing people and release the prisoners. There are still more than 12,000 political prisoners detained, and I was one of them. We should continue paying attention to Burma.

RFA: There are some reports that the Japanese government has some business dealings with the junta, and activists are calling for it to cut funding to the junta. What should the Japanese government do?

Kubota: As many activists have pointed out, an organization called the Mekong Watch has also repeatedly pointed out the fact that Japan is being used by the junta. As Japanese citizens, we should be very responsible, and we need to speak out. At the same time we should accept as many refugees as possible from Burma. We haven’t even tried to accept any refugees. The number of refugees in Japan is very small, even though Japan is a country that signed the Refugee Convention.

RFA: Since the coup, the military has targeted not only anti-regime activists but also the media and journalists. Why do you think this is?

Kubota: They arrest and kill journalists in Burma because they want to cover up their ongoing brutality. They don’t want to let the world know about the massacre.

RFA: Will you ever go back to Myanmar?

Kubota: I really wish I could. I really want to support the people of Burma, but currently I cannot enter the country anymore. I might be able to go after the country becomes a place where I won’t be arrested, even though I was filming the protest. I really hope that the country will become a truly safe place for journalists so that we can do our jobs. But there are still many Burmese people working in the country, even though it’s extremely dangerous for them. I have enormous respect for each of them.

Written in English by Roseanne Gerin. Edited by Malcolm Foster.

[圖擷取自網路,如有疑問請私訊]

|

本篇 |

不想錯過? 請追蹤FB專頁! |

| 喜歡這篇嗎?快分享吧! |

相關文章

AsianNewsCast